By Kate Masters

(VM) – For more than two years, COVID-19 has largely monopolized the time and resources of local health departments across Virginia. But as the virus moves into an uneasy plateau, health officials are turning their attention to another infectious disease with alarming rates of growth.

Since at least 2016, cases of syphilis — a sexually transmitted disease once thought to be on the verge of eradication — have been rising across Virginia. Cases increased by 158 percent between 2007 and 2017, according to data from the Virginia Department of Health, and rates jumped again the following year. In 2020, the most recently available data, there were 1,288 new diagnoses of early-stage syphilis, an increase of 228 cases compared to just four years earlier.

Even more concerning has been a persistent rise in congenital infections among infants who contract the disease from their mothers. A decade ago, in 2011, Virginia had zero cases. In 2020, there were 15, including five syphilitic stillbirths. Preliminary data from 2021 indicates another rise, pushing the state to 17 cases, according to Oana Vasiliu, the director of STD Prevention and Surveillance for VDH.

Up to 40 percent of infants born to women with untreated syphilis are stillborn or die from the infection shortly afterwards. Babies that survive can have serious health complications, including jaundice, severe anemia and blindness. The rapid spread of the disease over the course of a few years has worried public health workers across the state, from on-the-ground specialists to the department’s top leadership. Dr. Colin Greene, Virginia’s newly appointed state health commissioner, identified syphilis as one of the agency’s biggest post-pandemic priorities.

“It’s hard to believe we’re seeing a resurgence to the point where we’re seeing congenital cases again,” he said at a meeting earlier this month. “They’re something I was taught in med school that I’d probably never see because they used to be so rare.”

While the numbers may seem small, experts say they can obscure the seriousness of rising infections. In a fact sheet for health care providers, VDH described every case of congenital syphilis as “a sentinel event representing a public health failure.” Dr. Patrick Jackson, an infectious disease physician at UVA’s Ryan White HIV Clinic, said it’s because the disease is so easy to test and treat.

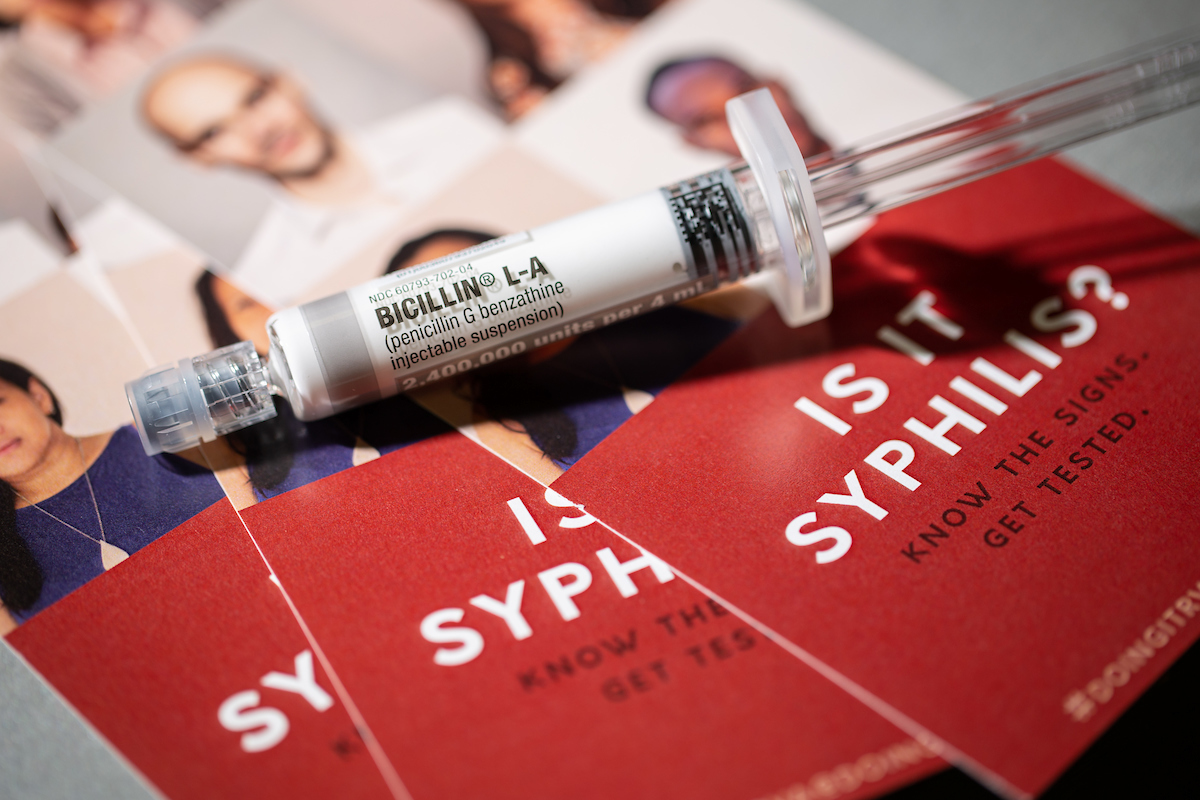

Federal guidelines call for all pregnant women to be tested at their first prenatal visit and sometimes later in the pregnancy, depending on risk factors. And as a bacterial infection, syphilis can be cured with a course of penicillin, which protects both mothers and their infants from serious complications. When congenital cases emerge, it’s a sign that women couldn’t access routine screening and other services that play a vital role in healthy pregnancies.

“We already know the United States has been doing a terrible job at prenatal care,” Jackson said. “If you’ve missed syphilis, you’ve probably missed a ton of other things.” The concern is borne out by state data, which shows that nearly 50 percent of all congenital cases from 2011 to 2020 occurred among mothers with late or inadequate prenatal care or no intervention at all.

The rise of STDs more generally is viewed as a bellwether of the United States’ underfunded public health system. While spending on prevention, in terms of dollars, has technically remained steady over the last two decades, purchasing power adjusted for inflation has fallen, according to analysis by the National Coalition of STD Directors. The strain on public health departments has coincided with the substantial rise in syphilis both in Virginia and across the country.

There are other theories for rising rates, including growth in online dating and speculation that condom use has fallen amid improved treatment and prevention for HIV — making the prospect of the disease less of a deterrent for unsafe sex (just over 40 percent of new syphilis diagnoses in 2020 co-occurred with HIV infections, according to VDH data). But Jackson said dwindling funding was the most logical explanation for the growth in cases.

Syphilis has always had a disproportionate impact on marginalized groups including Black and Hispanic Virginians and the LGBTQ community. But over time, rates have also continued to grow among other demographics, including women of childbearing age, a sign that the disease is spreading and going untreated among those women and their sexual partners. More intervention could help, but local health departments are often working with limited resources.

“In an ideal world, you’d be sending teams of nurses to vulnerable communities and making things super simple in terms of testing and treatment,” Jackson said. “And I’m sure the folks at VDH would love to do that sort of thing, but they have what they have.”

Staffing was already stretched thin…then came COVID

The frequent struggle to do more with less underscores the challenges of preventing STDs before they can spread. While syphilis can be detected with a simple blood test and cured with a routine antibiotic, the bacterial disease is known as the “great imitator,” Jackson said, thanks to symptoms that can mimic a range of conditions.

Primary syphilis, the earliest stage, is typically marked by small and often painless sores that can be easy to miss depending on where they emerge. Secondary syphilis can cause symptoms including rashes, fever and fatigue, but those will go away after a few weeks even without treatment. If the disease isn’t caught in its early stages, it can linger for decades. Jackson said 15 to 20 percent of patients will go on to develop tertiary syphilis, which can result in painful lesions, hearing loss and neurological symptoms like dementia.

Still, even early stages can lead to serious symptoms and even hospitalization. Over the last few years, Jackson said he’s noticed a rise in ocular cases — which can cause permanent blindness, — regardless of the patient’s age or stage of disease. That makes early detection key, but it rides on testing and building trust with patients. On the local level, the work is often done by disease intervention specialists, who follow up on positive results, share information about the diagnosis and refer people to free treatment at the health department or other community providers.

It’s not always easy. Like many other conditions, cases of syphilis and other STDs occur disproportionately among communities of color who may already be distrustful of the medical system. Workers are still grappling with the legacy of the Tuskegee syphilis study, which withheld treatment from nearly 400 Black men infected with the disease. And the stigma attached to sexually transmitted infections already makes some patients reluctant to speak with health officials, said Bradley Cox, the STD program coordinator for the Richmond-Henrico Health Department.

“If I were to sit down and say, ‘Hi, my name is Brad and I need a list of everyone you’ve had sex with in the last 12 months,’ not a lot of people are going to be very enthusiastic about participating in that,” Cox said. So while early intervention and treatment is crucial for identifying exposed partners and preventing more spread, it’s a job that takes time and expertise.

For most departments, the responsibilities are spread among a finite number of staff. Richmond leads the state in syphilis infections, but Cox currently has four full-time disease intervention specialists handling cases across the city as well as the Henrico and Chickahominy health districts, which, all combined, recorded a total of 245 new syphilis diagnoses in 2020. The same staff are responsible for following up on HIV cases, as well.

COVID-19 was an added stressor. Until recently, Cox had the funding for five specialist positions, but lost some staff due to turnover and promotions during the pandemic. When COVID hit Virginia, local health agencies were also forced to put other work on the back burner. Cox said his team worked hard to maintain follow-up services for syphilis, but clinical hours for testing and treatment were reduced as the district stood up coronavirus-related events. In the early days, especially, his team was shifted to case investigation and contact tracing for the emerging new disease.

“I myself actually spent some time going out to the Peninsula health district in Newport News to help them work on their very first contact tracing efforts,” Cox said. “In those early days of the pandemic, we were pulling people from wherever we could get them.”

The state’s STD testing data highlights the shifting focus. In 2020 and 2021, there was a 24 percent decline in the number of average monthly tests compared to the two years prior. It’s likely the trend was short-lived, and testing so far this year is closer to pre-pandemic levels, according to Tammie Smith, a spokesperson for VDH. But given the lag during the pandemic, some officials are still afraid the state is facing blind spots when it comes to new cases.

Cox pointed to chlamydia as one example. While new gonorrhea infections soared in 2020 and syphilis remained largely unchanged despite the decrease in testing, chlamydia rates suddenly and inexplicably took a nosedive. Of the three, it’s also the least likely to result in noticeable symptoms. Cox said the decline likely had less to do with a true reduction in transmission and more to do with a drop in the number of people being tested for the disease.

Like many health officials, he’s hoping Virginia will avoid another COVID surge, allowing local agencies to continue shifting their focus back to other vital day-to-day work. The rise in gonorrhea is a new frontier of concern, especially after Richmond-Henrico was forced to cut back tracing efforts during the pandemic. And unlike syphilis, it’s a disease that’s developed resistance to many of the antibiotics used to treat it, making new infections particularly hard to combat.

But syphilis still remains a major concern. In 2021, the state’s health department assembled a taskforce to review congenital cases of the disease along with examples of HIV passed from mother to child. The goal, according to Smith, is to review whether there were missed opportunities to prevent the disease and find ways for improving pre- and post-birth care throughout Virginia.

Thanks to more than $4.5 million in pandemic emergency funding, the state will also be hiring more than 30 new disease intervention specialists and six coordinators to expand STD prevention efforts. While the one-time allocation is set to expire in 2025, for Cox, it will mean doubling his full staffing from 5 to 10 positions.

It’s not clear whether it will be enough to reverse the state’s ongoing growth. But for local health departments, it could make a real difference in connecting with more patients.

“Folks who are disproportionately impacted by STIs — those communities are the same communities who are disproportionately impacted by things like lead poisoning and air pollution and other co-occuring conditions,” Cox said. “And it really speaks to why we want to focus on population health and what we can do to address the barriers that are keeping them from accessing the medical system.”

Reprinted from Virginia Mercury