By Sarah Vogelsong

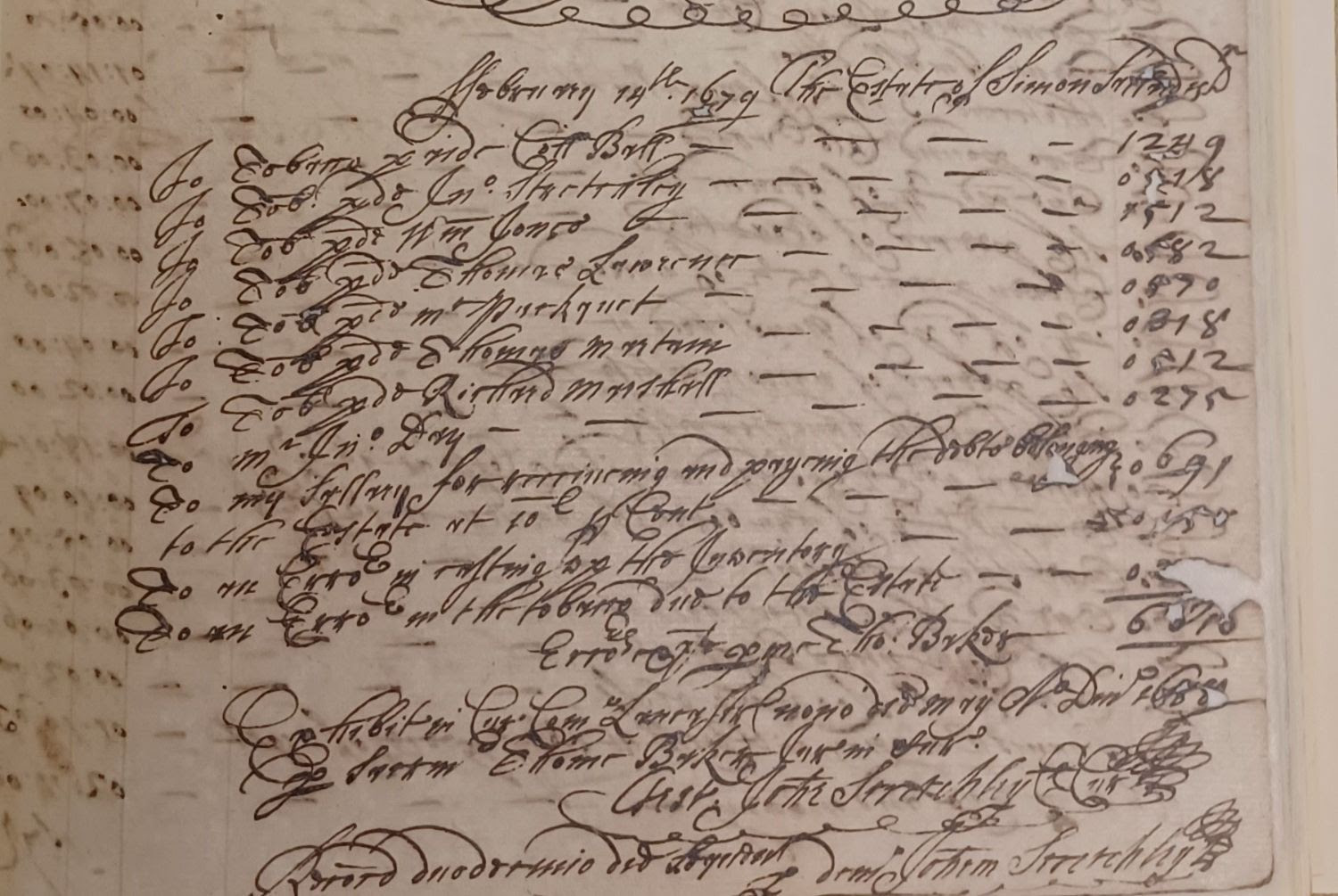

(VM) – Virginia is home to some of the nation’s oldest documents, squirreled away for centuries on the shelves of its 120 circuit courts.

But encasing many of the pages of the volumes stored on those shelves is an unlikely and unwelcome material: a form of plastic known as cellulose acetate that was used between the 1930s and 1990s to laminate aged and delicate documents. Once seen by archivists and conservators as a cutting-edge form of preservation, cellulose acetate lamination today is known to be a major threat to the conservation of documents because of the damage it causes over time.

“If not addressed now, records that managed to survive three centuries of wars, courthouse fires, and natural disasters will not survive another three centuries,” said a report from the Library of Virginia to the General Assembly this December.

So far, the Library of Virginia has found more than 1500 volumes of documents laminated with cellulose acetate in circuit court collections. Most of those are concentrated in the eastern part of the state, with especially large numbers in Richmond County on the Northern Neck (142 volumes), Essex County (91) and Chesapeake (80).

“These are the oldest records of the locality,” said Greg Crawford, state archivist and director of government services for the Library of Virginia. “These are records that date back to the early 1700s and even the 1600s in some cases.”

To date, Crawford said he isn’t aware of any Virginia documents that have been wholly lost because of damage associated with cellulose acetate lamination. But because restoring records laminated with the material is a lengthy and costly process, the library has over the past few years been working to increase awareness of the problem so circuit court clerks can secure funding to fix it.

“It’s not something that can be done in a couple of weeks,” he said. “It’s a very small number of conservators who can do this type of work.”

Cellulose acetate lamination wasn’t unique to Virginia. States up and down the East Coast enthusiastically adopted the practice beginning in the 1930s as the newest innovation in the field of records restoration.

“At the time in the 1930s, the 1940s and the 1950s, it was believed to be something that was good, something that was valuable,” said Crawford. “At one time asbestos was thought to be good.”

Virginia, however, was home to one of the most prominent champions of the process: William J. Barrow, a Brunswick County native who became a major figure in records conservation and for several decades ran the Barrow Restoration Shop out of the Library of Virginia, then known as the Virginia State Library.

During the 1930s, the National Bureau of Standards and National Archives began recommending cellulose acetate lamination as a key tool for records conservation. The process was both “harsh and destructive,” said librarian Sally Roggia in a dissertation on Barrow for Columbia University in 1999.

“The document was sandwiched between sheets of cellulose acetate and then subjected to both high pressure and high heat,” wrote Roggia. “The plastic foil was thus melted and forced into the document itself.”

Barrow became interested in the process while working at the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News. After the National Archives constructed a massive, hydraulic laminating press to conduct cellulose acetate lamination on a large scale, Barrow built his own incorporating rollers. His prototype, Roggia reported, “was homemade at Mariners from surplus ship parts of heavy gauge steel.” He later also established a press at the Virginia State Library in Richmond.

As time passed, cellulose acetate lamination was used by more and more conservationists.

“Libraries and archives that had the means purchased their own hydraulic presses or one of Barrow’s patented roller laminators,” the Library of Virginia noted in a fall 2018 newsletter for Virginia’s Circuit Court Records Preservation Program. “Thus began the cellulose acetate lamination craze that swept the nation.”

If the lamination process seemed too good to be true, it was.

Over time, cellulose acetate can cause documents to become discolored, clouded, warped or brittle. A vinegar odor, said Crawford, is a sure sign deterioration is occurring.

Getting rid of the old lamination isn’t easy, however. Unlike more modern restoration approaches that put a premium on “reversibility” — the idea that anything done to a document today should be able to be easily reversed — cellulose acetate can become permanently adhered to paper fibers if lamination is left long enough.

The Library of Virginia report to the General Assembly called removal “meticulous and time consuming, taking anywhere between three months to a year to remove cellulose acetate from one volume.” The estimated cost of treating the roughly 1,500 volumes in Virginia laminated with the plastic is between $15 million to $20 million over the next decade and a half.

“You’ve got to be almost like a chemist,” said Crawford. “There’s a lot of variables in this situation. When was this laminated? Was the paper de-acidified prior to lamination? They were constantly rejiggering the ingredients for this over the decades.”

Crawford said he believes the necessary restoration work can be carried out over the next 10 to 15 years using grant funds from the Circuit Court Records Preservation Program, which is funded by the General Assembly and overseen by the Library of Virginia.

The most recent state budget, which also required the library to report on the extent of cellulose acetate lamination in the commonwealth, puts just over $1 million in each of the next two years toward the program.

“It’s a lot of volumes,” said Crawford. “It’s a lot of intense work that’s involved.”