Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Clayton State University

Anonymous tips about inaccurate citations on the CV of Clayton State University’s first Black female provost led to her firing. Some observers believe the complaints were motivated by more than earnest concern for academic integrity.

By Kathryn Palmer

Clayton State University fired its first Black female provost nearly six months after she took the job.

While university officials say it was because an investigation found multiple inaccuracies on Kimberly McLeod’s curriculum vitae, observers inside and outside the metro-Atlanta institution believe her experience may be part of a larger trend in higher education.

“When I first heard about this, my mind quickly went to Harvard and what happened up there,” said Matthew Boedy, president of the Georgia Conference of the American Association of University Professors and an associate professor at the University of North Georgia. “It’s the same type of playbook.”

Clayton State University

He was referring to the forced resignation of Claudine Gay as president of Harvard University and the “playbook” that involves drumming up discrepancies about an administrator’s past academic work. It’s a strategy that has been deployed against a handful of academics—the majority of them Black scholars whose work focuses on race and equity—over the past several months.

Gay, the first Black president of Harvard, resigned in January partly because of plagiarism allegations first asserted by Christopher Rufo, a conservative activist who’s spoken publicly about the “playbook” he used to spur Gay’s resignation as part of his crusade to “eliminate the DEI bureaucracy.”

Gay also submitted corrections to her work even as some academics questioned the seriousness of the infractions.

While there’s no evidence that Rufo was involved in McLeod’s firing at Clayton State, the details of her case raise similar questions about whose academic work gets closely scrutinized and how these cases shape public perceptions of an institution’s ability to uphold academic integrity.

That’s especially important in a state such as Georgia, where tenure protections have been stripped down and efforts to diminish diversity, equity, and inclusion programs are underway.

“The more that higher ed is seen as not being able to police itself and hold itself accountable,” Boedy said, “the more you will see board of regents and legislators and Christopher Rufo step in.”

Boedy doesn’t know who submitted the complaints about McLeod’s CV that ultimately led to her termination, “but clearly there were people who did this work to find these problems with her CV,” he said. “Why they wanted to do that, I don’t know. My guess is they weren’t doing it out of the goodness of their heart for a transparent higher education system.”

‘Someone Who Understood’

When McLeod took the job at Clayton State last July, she became part of the 5 percent of provosts who are Black women. Her arrival signaled the continuation of a new era at Clayton State: The student body is more than 60 percent Black, but the 55-year-old institution didn’t hire its first Black president until 2021.

“What we’ve been doing in the past hasn’t really worked,” said a faculty member who did not want to be identified. They’d hoped the new provost would address the university’s declining enrollment and low graduation rates. “We need fresh eyes and ideas. Someone from outside could give a different perspective on things and would be open to new ideas. That’s exactly what (McLeod) did.”

And her 21-page CV indicated that she likely had enough experience to make long-term improvements at Clayton State, where racist microaggressions are commonplace and Black faculty aren’t always afforded the same opportunities to move into administration, according to the professor.

McLeod, who left her job as associate vice president of economic and academic development at Texas A&M University at Commerce to oversee academic affairs at Clayton State, earned a doctorate in education in 2002. She’s also worked as a college dean, professor, and public school administrator and teacher. Many of the more than 40 publications, which include a range of articles and books listed on her CV, explore topics related to improving educational outcomes for first-generation and Black students.

All of those accomplishments helped McLeod get the job over the white internal candidate, Jill Lane, a longtime Clayton State administrator who served as interim provost until McLeod came on board. Lane is now associate vice chancellor for academic innovation at the University System of Georgia.

Under McLeod’s brief leadership, “It felt like we were actually going to make some changes instead of just talking about it,” the professor who requested anonymity said. “Clayton state finally had someone who understood the student population.”

However, “a handful of people who apparently have a lot of power were really resistant to her from the beginning,” the professor said. “My issue with that is when she was interviewed, the search committee carefully vetted her background before she got the job. Yet, a few concerned faculty members had enough power to create intense scrutiny of her background.”

The Investigation

Within months of McLeod’s historic appointment as Clayton State’s provost, the University System of Georgia Ethics and Compliance Reporting Hotline received numerous anonymous reports that McLeod did not have a part in authoring six of the publications listed on her CV.

The university system subsequently opened an investigation.

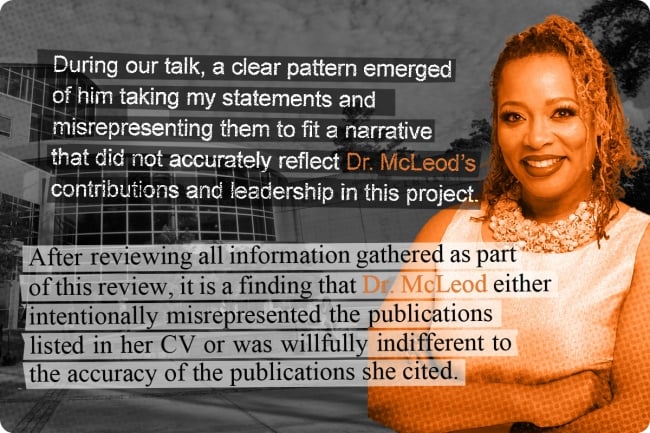

“It was a finding of this review that each of these citations were inaccurate and, in some instances, referenced journal articles that were never published,” concluded the final report Inside Higher Ed obtained through a public records request. “After reviewing all information gathered as part of this review, it is a finding that Dr. McLeod either intentionally misrepresented the publications listed in her CV or was willfully indifferent to the accuracy of the publications she cited.”

Two of the publications in question were research articles written for the state of Texas; a third paper was written for Harris County, the most populated county in Texas. On her CV, McLeod listed herself as a co-author for all three articles, yet a review of the actual publications did not include her name in the citations.

According to the review, the Georgia University system’s investigators asked McLeod about these inconsistencies. While McLeod, who was already a tenured professor when the papers were published, insisted she contributed work on all of them, she said one of the articles didn’t have her name on it because she wanted her co-author, assistant professor Kamshia Childs, to “take all of the credit for the article” to help her obtain tenure.

Investigators also interviewed Childs, who initially “stated that she did not authorize anyone else to receive credit for the publication,” according to the report. However, Childs sent Wesley Horne, the chief ethics officer who interviewed her, an email right after their call ended to clarify that “ALL of the work was shared work, and could be cited as such.”

Horne responded: “I understood from our call that you did not give anyone else permission to list themselves as an author.” Childs told him that was incorrect. “I did not say that, and that is why I wanted to provide clarity,” she wrote. “We all worked through the planning and editing process together. Yes, I was the primary writer, but we also mutually agreed that this work as a whole was all of our work.”

‘Did Not Seem Neutral’

Childs was not the only co-author of McLeod’s who took issue with Horne’s investigation.

“During our talk, a clear pattern emerged of him taking my statements and misrepresenting them to fit a narrative that did not accurately reflect Dr. McLeod’s contributions and leadership in this project,” Darlene Breaux wrote to Jenna Green Wiese, vice chancellor for internal audit, ethics and compliance at the University System of Georgia, in filing a formal ethics complaint against Horne. “His tone with me did not seem neutral or of someone who was simply fact-finding.”

Horne forwarded Inside Higher Ed’s inquiries about the investigation to the university system’s communications team, which declined to comment on “personnel matters.””

In response to questions about another inaccurately cited article listed on her CV—McLeod inserted hers and Child’s names and removed the names of the other authors originally cited in the publication—she also said that while she contributed to the work, she left her name off to support the tenure goals of her colleagues. She got the names of some of her co-authors wrong because she “relied on her memory as to who actually completed work on that publication,” according to the report.

Marta Mercado-Sierra, one of McLeod’s co-authors on the reports, emailed Horne the correct format for the citations, which included McLeod’s name and told him that she was in the process of having the publications corrected.

As of Thursday, two out of the three reports the university system investigated now cite McLeod as an author.

Investigators also found misrepresentations of three peer-reviewed articles McLeod took credit for on her CV.

One listed McLeod as a co-author, but the actual article made no mention of McLeod and was published in a different journal than the one listed on her CV. When questioned by investigators, McLeod explained that she had a minimal part in producing the article and that she wrote the entry on her CV based on an email another faculty member sent informing her that it had been accepted for publication.

While faculty involved with the publication acknowledged that McLeod had contributed to it, there was no record that they’d told her it was accepted for publication.

Another entry on McLeod’s CV said she’d co-authored an article published in the Journal of College Student Affairs. However, no such journal exists. There is a College Student Affairs Journal, but it rejected the submission. A professor interviewed by investigators said the paper, which McLeod worked on, was submitted to another journal, but there’s no record that she was told it was accepted.

A third entry on McLeod’s CV listed an article about African American college students’ sexual attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs published in the Journal of Black Studies. Investigators found the journal had rejected the submission.

“At the time she left, she believed they’d been submitted and accepted for publication at two different journals,” Travis Foust, McLeod’s lawyer, said. “This was the CV she was preparing while at Texas A&M Commerce—while these were sort of outstanding—and submitted to Clayton State and got the job. These events that transpired to make these citations incorrect either happened while she was leaving or afterwards.”

McLeod declined to be interviewed for this article, but Foust said she acknowledges the flaws in the way she cited the articles in question.

However, “There’s no indication that any of these six articles were instrumental in her getting the job at Clayton State,” said Foust, who added that the investigation seemed outcome-driven. “They weren’t the reason she got the job. Her experience is why she got the job.”

Foust said his client’s immediate goal is to get her academic record cleared, but that she may pursue litigation if that’s not successful.

“It’s hard to ignore that this happened at the same time that the university was being led by a Black president and Black provost for the first time,” he said. “If there is litigation, (discrimination) will be a significant part of it.”

McLeod’s appointment as provost also came with a full, tenured faculty position in the psychology department, but since she hadn’t passed the university’s probationary period, she didn’t have the full protections of tenure.

‘Very Odd’

Since McLeod’s termination in December, faculty have reacted with “shock and surprise,” according to a second anonymous professor.

“I wonder why so much emphasis was placed on minor details of her scholarship. I really wonder if this was done because of race and gender,” the professor said. “Her vita spoke volumes regarding her work on issues pertaining to race and gender. I wonder if some people took pause with her work.”

Jonathan Bailey, a plagiarism consultant and author of Plagiarism Today, said he doesn’t fully understand some of McLeod’s explanations for the misattributions on her CV.

“If you admit that you worked and contributed on a paper in order to deserve authorship and you ask yourself not be put on it, that’s a different type of issue,” he said, noting that intentionally omitting an author can raise questions about the integrity of the research, too. “It’s very odd to remove yourself from a paper. That’s almost never done in academia.”

Bailey said that even though only a small portion of McLeod’s total publications had flawed attributions, intent should be the focus of any plagiarism investigation. “Was this clearly a deliberate act to attempt to take credit for work of others that she didn’t do?” he said. “My experience has been that people who mislead once rarely do it just once. Typically, the lies just get bigger and bigger.”

But if it can be attributed to a mistake, Bailey said he’d be more likely to give the accused plagiarizer the benefit of the doubt. And that’s the kind of nuance that is often missing from recent high-profile instances of plagiarism.

“All plagiarism is bad, but not all of it needs such an extreme response,” he said, adding that the definition of plagiarism is very broad. “We are seeing a lot of weaponization of plagiarism. It’s seen as an easy way to damage someone’s career or get them removed from a position if you don’t support them politically or ideologically.”

While scrutinizing each line of one person’s CV may not take long, applying that level of scrutiny to every person a university hires may not be feasible.

“Universities have struggled to try and do these thorough checks,” Bailey said. “Someone who’s launching a targeted investigation isn’t risking a significant amount of time. They may have the ability to focus on and analyze that one person’s work.”

The risk of selectively calling attention to plagiarism, he said, is that “the standards will be applied unevenly.”

‘Poisonous Patriarchy’

Black women administrators have long faced structural barriers to rising up the ranks of academia.

Jabari Simama, former president of Georgia Piedmont Technical College, cited McLeod’s firing, Claudine Gay’s resignation, and the suicide of Antoinette Candia-Bailey, an administrator at Lincoln University of Missouri, in a February article for Governing Magazine and described their experiences as examples of “the poisonous patriarchy of higher education” that targets Black women in particular.

“In too many cases, African American women, who constitute only a tiny percentage of college administrators and instructors, say they face hostile environments and complain that they are subject to microaggressions, racism and sexism,” Simama wrote. “The loss of Black female talent has even larger implications for African American students at places like Clayton State where African American women constitute a majority of those enrolled.”

In evaluating McLeod’s case, he said higher education officials should ask themselves: “What constitutes ‘qualified’ in the first place, particularly at regional colleges like Clayton State that emphasize teaching over research?”

The university appears to have found another qualified Black woman to take McLeod’s place for the time being. On Monday, Clayton State announced that Corrie Fountain, associate provost for faculty affairs at Georgia State University, would take over as interim provost until the university hires McLeod’s permanent replacement.

Both Clayton State and the University System of Georgia declined to comment on whether they closely scrutinized McLeod’s CV prior to hiring her. They also declined to comment on how this situation may change how they vet future candidates.

But Sheila Smith McKoy, a higher education consultant who has served as a top administrator at multiple institutions, said additional scrutiny of job candidates undermines the quality control checks academia already has in place.

“There has always been a rigor in academia,” she said, noting that earning tenure comes after years of a faculty member having their research scrutinized and evaluated by their peers. “The other subtext here is the tendency in many parts of our country to try to eliminate tenure.”

She said the stakes are even higher for Black women who aspire to positions of leadership.

“There’ve been many successful Black women who have served without issue,” Smith McKoy said. “But the scrutiny is more intense. And in that, they become symbolic of why you can’t have women in these positions, and in particular why women of color should not be in these positions.”