By Rachel Mahoney

CN – In the 70 years since the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case banned racial segregation in U.S. schools, the pursuit of quality and equitable education in Prince Edward County has taken many forms and faced many challenges, and continues strong today in its legacy and impact.

As one of the five civil rights cases that were combined in Brown, Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County brought together the lion’s share of individual plaintiffs decrying the “separate but equal” doctrine as a farce — about three-quarters of more than 200 people named in Brown.

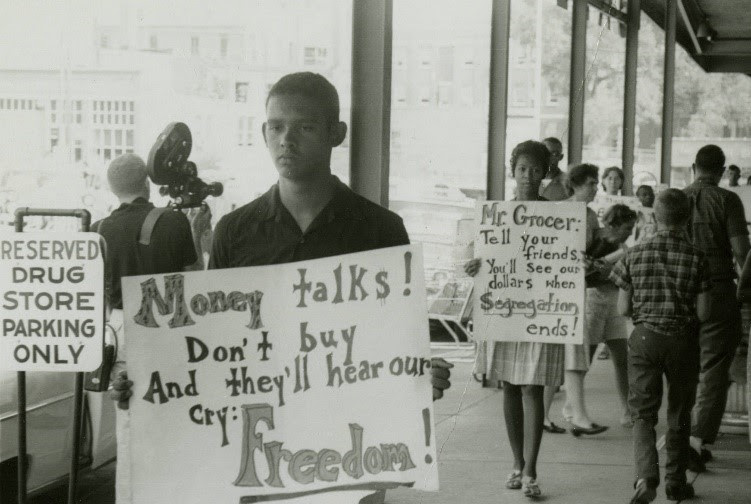

They were the students and families of students who were squeezed into Robert Russa Moton High School in Farmville at more than twice its capacity, who suffered leaking ceilings and inadequate heating and took their classes in a broken-down school bus or hastily built tar-paper shacks. With a spark of momentum from student protests in 1951, 16-year-old student Barbara Johns led a student strike for equal education and started blazing a long trail out of Moton that turned the status quo on its head and ignited passions about strengthening access to education.

In many ways, Brown was only the beginning.

During the course of the Davis case, county officials built a new schoolhouse in 1953 for Black students. And though the hundreds of Prince Edward plaintiffs won their case in 1954 once it reached the U.S. Supreme Court as part of Brown, the win was yanked out from beneath their feet in 1959 when the county, like so many other Virginia localities, shut down its schools rather than let Black students learn alongside their white counterparts.

“Our [basketball] coach in the spring said to take everything out of your locker because we’re not sure what was going to happen in the fall as far as the school,” Phyllistine Mosley recalls of her sophomore year at Moton.

Some students ended up stuck in a holding pattern. Despite the fervor and community solidarity Johns helped grow, and with the new school sitting vacant, some families didn’t want to send their kids out to learn in hostile or unknown environments.

Not so for Mosley. Adventurous and backed by a supportive family, she was one of about 60 Prince Edward students to move down to Kittrell College nearly 100 miles away in North Carolina and continue to focus on her schooling. And it was possible because of that solidarity in Prince Edward’s Black community, meeting and planning and working connections.

“It was just families working together and following each other, those that agreed to allow their children to leave home. … That was a big decision that families had to make,” she said.

Then, she opted for a change of pace for her senior year, moving in with a white Quaker family in Yellow Springs, Ohio, and learning in an entirely different environment.

“They kept us busy, they kept us involved, and so we didn’t really have time to be homesick because of the attention that they gave us. … It was just like a different world,” she said.

By the time her hometown was finally forced to integrate its schools in 1963, Mosley had moved on to Bennett College, a school for Black women in Greensboro, North Carolina. Segregation proved to be dogged: Mosley’s mother had to travel to Richmond to become a nurse as a Black woman and help put her children through college, her sister continued to take part in area demonstrations, and Longwood College seized land from Black owners through eminent domain.

As someone who survived Massive Resistance, Mosley has lived out a commitment to exposing people to new ideas and expanding access to education — first by working as an extension agent in Campbell County and then, after retirement, as a “professional volunteer” in the greater Lynchburg community.

Lessons from the fight for equitable education have been passed down to younger generations. Cainan Townsend knows them well: His father, Earl Townsend, started first grade at age 10 when Prince Edward County’s free schools opened and graduated high school at 22, older than his senior English teacher.

Each summer after school, Cainan Townsend would be busy continuing his studies in summer school or with homework his father would hand him.

“As a kid I was frustrated, but then as an adult I finally realized just because he lost so much of his education and he was locked out of school, he feared that [summer] melt experience,” he said. “He always pushed me academically.”

Later, studying at Longwood University — where he was sometimes the only Black man in class — he said he was embarrassed to finally realize Prince Edward County’s ties to the Brown case. And it was only about 10 years ago that he learned that his great-aunts had taken part in Johns’ protests and his great-grandfather was among the Brown plaintiffs.

“I was pretty upset because why do I know about my father and his siblings … but why don’t we talk about my great-grandfather being a plaintiff in this case?” he said. “So I pretty much made it my mission then to make sure that I talk about it whenever I get a chance and to talk about the impact that these families had on Davis, on Prince Edward County, but also Brown.”

Now, as executive director of the Robert Russa Moton Museum, he does exactly that. Beyond ancestry research to confirm his family members’ legacy, Townsend said building out the full and complete narrative of Prince Edward’s integration has been at times a difficult, yet important goal.

“Culturally, [this] just wasn’t something that was talked about,” he said. “The school closures part in particular wasn’t talked about enough because it’s painful.”

With exhibits winding through renovated classrooms in the 1953 school building and an immersive short film about Johns playing in the auditorium, Moton today is a product of continued work to bring that history to light.

The work of Martha E. Forrester’s Council of Colored Women, founded in 1920 to improve access to education for Black students, paved the way for its spiritual successor, the Council of Women, to purchase the property from the county in 1996. Townsend counts a timeline of milestones for the museum since 2008: major fundraising for renovations, partnering with Longwood University, recognizing Johns in Virginia SOLs and through a monument in Richmond, and Prince Edward County revising its seal to feature Moton in 2022, to name a few.

“The only color that really matters in this story, you know what it is? Green,” he said. “People seeing the value in civil rights tourism has I think has really moved the needle for us here. …

“I’m glad the needle is moved. Now you see all the government officials and the county sharing this history, talking about Barbara Johns and this history. … It’s been amazing to see.”

Federal and state funding continues to fuel maintenance costs for Moton, which Townsend envisions as a hub for civil rights history education and research.

He’s also been building connections across the “Brown Five,” other schools in Delaware, South Carolina, Kansas and Washington, D.C., that were central to the cases combined in Brown. The sites were officially linked in 2022, and Townsend said he’s been visiting them and helping fill out a broader narrative around Brown.

“That really has transformed the way in which we talk about this story,” he said. “It’s been really cool to see the plaintiffs from the cases interact with each other in a way that they haven’t before.”

Another important prong of Moton’s work has been in outreach to the descendent community, one Townsend said is a challenge in part because of how far-flung it is today. Involving children and grandchildren of that “locked-out” generation helps ensure Moton’s story still is being recorded and interpreted in an authentic way, and Townsend said he’s ”very mindful that we’re losing this population.”

To that end, Moton will recognize a major moment on Sunday, when Longwood is set to recognize those disenfranchised Black community members with honorary doctorates as a special part of its commencement.

Among the honorees will be Mosley. Having received her honorary diploma from Moton in 2003, the honorary doctorate will be even more historic for her.

That’s because Mosley counts 120 years of service to Longwood between her father, grandfather and great-grandfather working as bakers, all the way back to when it was called State Female Normal School.

She recalled seeing how “royally” the students were treated there, but there was no sense comparing the life of those white girls to her own, and “it didn’t bother me because I knew we couldn’t go to the college.”

Around that time, Mosley had her sights set on getting out of Prince Edward, always looking forward and seeking new opportunities. This time, she’ll be returning for a reconciliation over why that was necessary for her in the first place.

“It’s great that they’re recognizing the fact that we missed out on a lot, and a lot of things were taken away from us by closing the schools,” she said. “A lot of students still feel bitter. I don’t feel bitter, but I know what happened, and it wasn’t right.”