(VM) – A final report, nearly a year in the making, recommends changes to teacher training, graduation requirements and curriculum to reform how Black history is taught in Virginia schools.

The report was published this by the Virginia Commission on African-American History Education, which was established by Gov. Ralph Northam by executive order last August, on the same day he spoke at an event commemorating the arrival of the first slaves at Fort Monroe more than 400 years ago and a little more than six months after a photo of a person in blackface and another in a Ku Klux Klan costume was found on his medical school yearbook. (Northam initially said he appeared in the photo, then denied he was either of the people depicted.)

The final recommendations come as Virginia, like the rest of the country, grapples with a legacy of racism and ingrained social inequities brought to the forefront by the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer in May. Less than a month later, Northam announced his intention to remove the state’s largest Confederate monument, a 60-foot statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee in Richmond — a process that’s been delayed by multiple lawsuits. Other Confederate monuments across the state have been felled by protestors or city leaders.

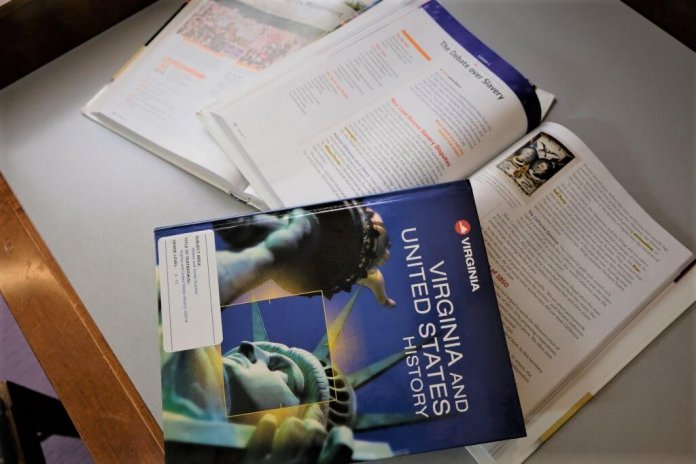

For years, state educators have also expressed concerns that Virginia’s textbooks and history education standards fail to accurately or adequately depict the legacy of slavery and historical contributions of African Americans.

“The standards were tainted with a ‘master’ narrative that marginalized race and the presence of non-Europeans on the American landscape,” said Cassandra Newby Alexander, a professor of history and dean of the College of Liberal Arts at Norfolk State University and a member of the commission, before the recommendations were presented.

“These historical silences skew our perspective of the past and erase people of color,” she continued. “And it supplants our nation with a false narrative that ignores the cultural underpinnings in American society.”

Virginia Secretary of Education Atif Qarni said the commission was established to overlap with the state’s regularly scheduled curriculum and standards review. The last update to history curriculum was made in 2015, and the report is intended to guide the revision of those standards in 2022. Other recommendations will likely be addressed legislatively when the General Assembly convenes for its regular session in January.

Three of the most significant suggestions would revise graduation requirements for Virginia students, create new training expectations for teachers and revise how important aspects of history — including slavery and the Civil War — are taught in schools.

Making it a graduation requirement

The state’s current history curriculum does cover slavery and important civil rights moments, but educators have often complained that the lessons lack context or gloss over events. One of the commission’s biggest recommendations would make African American history a graduation requirement for Virginia students.

Derrick Aldridge, chair of the commission’s professional development subcommittee and professor of education at the University of Virginia, said a newly established elective course could fulfill this requirement. Northam announced last week that VDOE had finalized the class, which will introduce students to “key concepts in African American history, from early beginnings in Africa through the transatlantic slave trade, the Civil War, Emancipation, Reconstruction, the Civil Rights era and to the present,” according to the release.

“Students will learn about African American voices, including many not traditionally highlighted, and their contributions to the story of Virginia and America,” it continued.

Teacher training requirements

Another key recommendation would require Virginia educators to be certified in black history, a process that requires completing specific coursework or exams.

“Over the past years, I’ve heard personally from teachers and future teachers who have told me they do not feel prepared to teach African American history,” Aldridge said at Monday’s meetings. The recommendation comes at a time when “students in Virginia and across the country are interested in learning about African American history in order to better understand the history of the United States,” according to the report.

Another suggestion would require every Virginia educator to certify that they enrolled in a cultural competency professional development course by 2022. The exact requirements haven’t been established, but the overall goal is training teachers to understand their own cultural perspective and address biases within the educational system. Learning how to sensitively address topics of race and discrimination is also key.

“In Virginia, teachers have been criticized for questionable activities meant to teach African American history and engage around difficult topics, such as through slave games and mock auctions,” the report reads. And while 52 percent of students in Virginia are people of color, 82 percent of teachers in local school divisions are White.

Adjusting history and social science standards

The commission recommended both technical and general edits to Virginia’s current standards of learning for history and social science to correct inaccuracies and provide important context. One concrete example is the state’s 11th grade history curriculum, which defines the causes of the Civil War as “cultural, economic and constitutional differences between the North and the South.”

Members described the language as “ passive, evasive and circular” in the report, recommending that new standards clarify that all of those differences were based in slavery. Other technical edits include adding important African American historical figures and adding or correcting coursework on slavery, the abolitionist movement, the Civil War, Reconstruction and lynching.

More generally, the commission recommended an overhaul of the state’s learning standards to ensure that African American history is treated as part of American history, not a separate component.