(VM) – Gov. Ralph Northam’s latest message to local school systems is to start thinking about reopening — and soon.

“In the short term, all of our school divisions need to be making plans for how to reopen,” he said at a news briefing on Thursday. “It’s not going to happen next week. But I want our schools to come from this starting point: how do we get schools open safely?”

Some division leaders said the new directive — accompanied by interim guidance from the Virginia Department of Health and Department of Education — represented a significant departure from the state’s earlier messaging on in-person instruction. Virginia’s initial guidance, released in July, emphasized that the final decision on reopening laid “squarely in the hands of local school boards” amid uncertain evidence on the role of children in COVID-19 transmission.

But a new letter from Virginia Superintendent of Public Instruction James Lane and state Health Commissioner Dr. Norman Oliver assured superintendents, school leadership and local health departments that “data increasingly suggest that school reopenings are unlikely to contribute significantly to community transmission when rates of community transmission are low and schools have infection prevention measures in place.”

The accompanying guidance includes a decision-making matrix that elevates individual mitigation measures over levels of community transmission. In a separate briefing later on Thursday, Lane said many divisions have been basing their reopening decisions primarily on top indicators from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which advise schools to consider community case rates and the percentage of positive tests over the last two weeks.

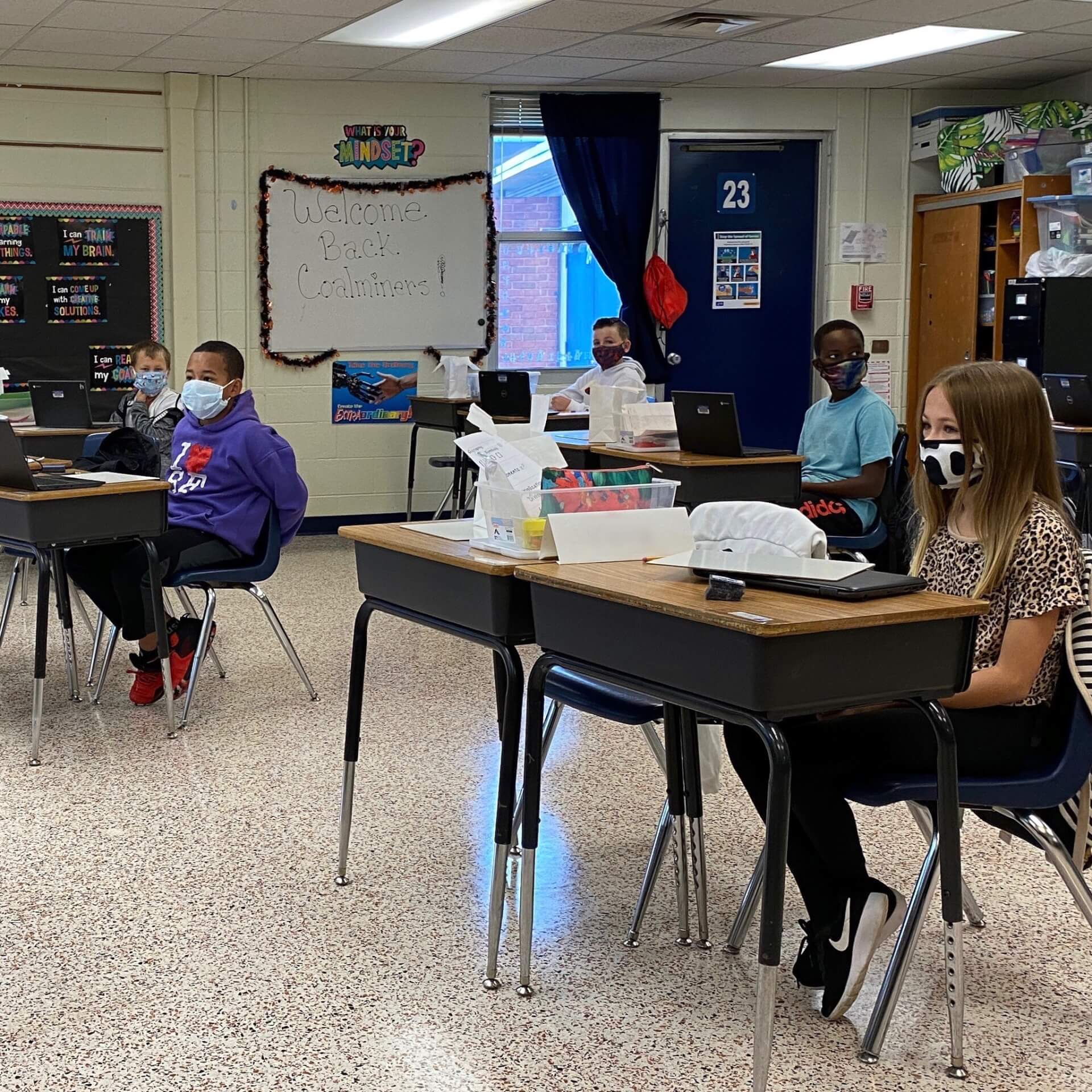

But Lane said heavier consideration should go to the ability of local schools to implement mitigation measures such as mask usage, sanitation and social distancing. Other main considerations include whether there’s evidence of spread within school buildings themselves, as well as the impact that school closures have had on the surrounding community.

“Even if they’re in the highest category of community transmission — and even more so for low and moderate — we recommend that they maximize in-person learning as much as possible,” Lane said.

The recommendations also call on schools to prioritize instruction for more vulnerable students, including young learners, students with disabilities and English language learners. And instead of making district-wide and long-term decisions — opting for remote learning over an entire quarter or semester, for example — officials say schools should have the flexibility to phase out decisions after a few weeks.

“If there’s low absenteeism, there’s no case transmission in buildings, your staff capacity isn’t strained — that school should have some in-person options,” Lane said. “If there’s an outbreak in a school, certainly think of closing for some time. But if there are no outbreaks and no transmission in the school community, we’re saying you should open as long as you can do mitigation strategies.”

However, as contact tracing resources have grown increasingly strained, most local health departments are prioritizing outbreaks and other cases that pose a significant public health risk. If multiple students or staff members test positive after close contact or sharing a potential exposure, health officials will likely investigate to determine if there was in-school transmission. But there’s little data on how most individual cases were contracted, and many local health officials have warned it’s become increasingly difficult to catch infected students or staff before they enter school buildings.

Reopening decisions have sparked fierce debate in local communities since Northam first announced a framework to bring students back to the classroom — four months after becoming one of the first governors in the country to close schools for the remainder of the spring semester.

Lane emphasized that the state never required schools to adopt remote instruction after releasing its first round of guidance in July. But those guidelines heavily emphasized CDC recommendations and asked schools to notify VDOE if they planned to deviate from the state’s framework.

By early September, the majority of local school divisions — 67 in total — had chosen to begin the fall semester remotely. As of Thursday, that number had dropped to 52. But Keith Perrigan, the superintendent for Bristol Public Schools in Southwest Virginia, said much of the ongoing caution stemmed from the original guidance, which took a more incremental approach to bringing students back to the classroom.

“This is a huge change,” he said. “The previous phase guidance, it was probably more of a recommendation to be cautious. And I think the new guidance is to try your very best to reopen. If you can mitigate appropriately, you ought to do what you can to get back in school.”

There’s still no mandate for school divisions to follow the state’s revised guidance. Lane said Thursday that the Virginia Constitution left the final decision with local school boards. But education officials also faced heavy criticism from some superintendents earlier this year for allowing local divisions to deviate from the original plan.

There’s still no mandate for school divisions to follow the state’s revised guidance. Lane said Thursday that the Virginia Constitution left the final decision with local school boards. But education officials also faced heavy criticism from some superintendents earlier this year for allowing local divisions to deviate from the original plan.

Some school systems have already made the decision to stay closed until at least the early spring — something Lane said he’d recommend reconsidering in light of the new guidance and the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines. But there are also continued debates even in districts that have prioritized in-person learning. In Chesterfield County, which announced plans to bring back elementary students next month, parents launched a petition calling on the school system to reverse the decision and keep schools mostly closed until teachers are fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

Both Northam and Lane faced significant questioning over the timing of the new guidelines, given that many schools have already announced reopening decisions for the spring. Virginia is also experiencing an ongoing surge of COVID-19 which some models suggest could continue until February. Rates of community transmission are consistently higher across Virginia than they’ve been at any other point during the pandemic. Daily new cases have risen in all five geographic regions throughout the early days of January, and hospitalizations are at an all-time high. Many health systems have voluntarily canceled elective surgeries or announced new surge plans to boost capacity for an ongoing influx of cases.

Lane said announcing the new guidance would give school districts the opportunity to prepare their plans in the coming weeks — even as Virginia contemplates longer-term changes such as year-round instruction to make up for learning loss during the pandemic. Northam also touted the arrival of COVID-19 vaccines as an important step in returning students safely to the classroom.

“While getting everyone vaccinated isn’t necessary to reopening schools, it will make it a lot easier,” he said. Eleven local health districts have begun vaccinating educators — or plan to start soon — after moving into Phase 1b of the state’s vaccine campaign.

But the timeline for the rest of the state remains unclear. As of Thursday, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ranked Virginia in the low bottom third of all U.S. states when it came to immunizing residents. The same day, VDH’s vaccine reporting dashboard showed that only about 25 percent of shots distributed across the state had made their way into patients’ arms.

And throughout November and December, some health districts advised in-person schools to again close their buildings, warning that the surging cases made it impossible for them to trace and investigate new infections. In Bristol, Perrigan said it was the first dose of vaccines — administered by the local health department earlier this week — that helped reassure teachers more than anything else.

“That’s what had the biggest impact — the availability of vaccines,” he said. “I think a lot of pressure was released once our staff was able to get that first round.”