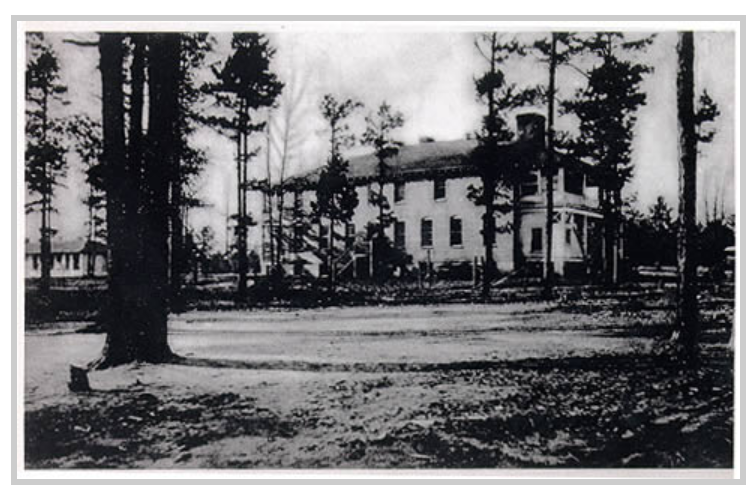

The Piedmont Tuberculosis Sanatorium , about 1918. Courtesy of the University of Virginia.

By Emily Hemphil

(CN) – A highly contagious disease swept across the country, rapidly becoming the single leading cause of death. All aspects of daily life were disrupted, and minority communities were disproportionately impacted with the only cure being to isolate and rest.

For Black Americans in the early 1900s, isolation and rest from tuberculosis meant confinement at the Piedmont Tuberculosis Sanatorium, located in Burkeville where the Piedmont Geriatric Hospital now stands. It served more than 12,000 Black patients throughout its almost 50 years of operation. It was also the only institution in the state that provided a two-year advanced training program for Black women to specialize in tuberculosis care.

Map by Robert Lunsford.

Now nearly 100 years after Piedmont’s founding, an application for a historical marker recognizing the site – submitted by the Tuberculosis Foundation of Virginia and Tom Ewing, history professor and associate dean of graduate studies and research at Virginia Tech – was approved by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources on June 17.

The description on the marker, written by Ewing, will read:

“Piedmont Sanatorium opened in April 1918 as the first public residential facility in Virginia for African American patients with tuberculosis. More than 12,000 patients from across the state were treated here over the next five decades. The sanatorium offered residents an open-air treatment emphasizing rest, a healthy diet, and limited activities, including occupational therapy. Piedmont’s nurse-training program, a two-year course that provided Virginia’s only advanced training for African American women in tuberculosis care, graduated at least 350 nurses from 1920 to 1960. In 1967, the facility became Piedmont State Hospital, and tuberculosis care was gradually phased out.”

The Piedmont Sanatorium was the sole medical institution for Black Virginians diagnosed with tuberculosis up until the late 1960s. Before its establishment, the only other treatment options were the Central State Hospital for Mental Diseases and the State Penitentiary. The more widely known tuberculosis sanatorium is the Catawba Sanatorium, now the Catawba Hospital of the Virginia Department of Behavioral Health and and Development Services, which exclusively served white patients. The origins of the Catawba Hospital have long been acknowledged with an entire hallway in the facility dedicated to providing visitors with various pictures, artifacts and information about its history. A historical marker for the Catawba Sanatorium has even stood alongside Route 311 since 1948.

None of this currently exists for the Piedmont Sanatorium.

“We definitely wanted to do this,” said Molly O’Dell, board member for the Tuberculosis Foundation and former Roanoke-Alleghany Health District Director. (Disclosure: O’Dell is also a member of our community advisory committee but committee members have no say in news decisions). “When I met with Tom, he told us a marker had never been erected. Since Catawba has one, we knew we had to do this.”

Ewing had been interested in Virginia’s tuberculosis sanatoriums for several years, doing research with his graduate students on Catawba and releasing several publications on the subject, but it was the events of 2020 that brought his attention to the lesser known Piedmont Sanatorium.

Black communities were disproportionately impacted by Covid-19 due to a variety of health, societal, and environmental disparities, but this virus is not by any means the first disease to exacerbate America’s systemic injustices. A report by the Virginia Health Department in June of 1935 stated that pulmonary tuberculosis was the cause of death for 946 Black Virginians and 817 white Virginians, though African Americans comprised only a third of the total population. Ewing believed it was past time to examine race and health in relation to one another.

“We’ve become aware of racial disparity in health outcomes,” he said. “Piedmont was unusual as a state institution that was deliberately and purposefully providing aid to African Americans and created a facility to provide treatment, but embedded all throughout was a racist double standard – why it was created, the treatment offered and who could work there.”

In the early 18th century, tuberculosis was responsible for around 10 percent of deaths in the United States, but the concept of a sanatorium originated in Europe. As no medication or vaccine existed to fight the disease, those diagnosed were removed from urban environments and sent to more remote places to hopefully recover with a combination of good nutrition and rest. In the U.S., state governments got involved in this process and began to establish and fund sanatoriums. The Catawba and Blue Ridge sanatoriums (the latter outside Charlottesville) were set up to treat white patients, but through the advocacy and support of Black organizations such as clergy, medical and other professional groups, the state Department of Health allocated the funds to found the Piedmont Tuberculosis Sanatorium.

However, in Virginia during the early1900s, it was an uphill battle to even find a location for the hospital. The health department purchased land from a railroad company near Suffolk, but faced such opposition from the white locals that they moved to Nottoway County, which had the highest percentage of Black residents in the state, though there was still some protest.

Ewing explained that there was a widespread, yet unarticulated understanding among officials about the need for a Black tuberculosis treatment center: wealthier, white families often had African Americans working in their homes, death rates were significantly higher among African Americans, so white populations needed to be protected from contagion.

Starting out with 20 to 25 beds in 1918, the medical facility grew to hold 200 by the 1930s. While the hospital itself was technically supported by the state, patients were still charged a weekly balance not covered by the government. Once again, Black businesses and churches worked to acquire the necessary donations to sponsor the ill. The Norfolk Journal and Guide, a prominent Black newspaper, maintained a record of the groups that were supporting individuals at the sanatorium.

The average stay at the hospital was 2 to 3 months as it was more logical, as well as financially beneficial, to keep patients longer so they would not relapse after leaving and return in a worse condition.

Even though some steps forward were taken by erecting the Piedmont Tuberculosis Sanatorium, racial inequities were apparent throughout. The superintendent, doctors and staff were all white and remained that way for all 49 years of operation. A movement for a Black doctor to be appointed rose in the late 1930s and early 1940s. The proposal was even approved by the state legislature in 1943, but the state Board of Health voted against it with the justification that there were not enough qualified African American physicians to hold the position. It is more probable that because some white patients who lived in the area received out-patient services at Piedmont, it would have been unacceptable for them to be treated by a Black doctor, according to Ewing.

Another discrepancy between the segregated sanatoriums was that more white patients in earlier stages of the disease were admitted to Catawba and Blue Ridge, thus more likely to make a full recovery. At Piedmont, however, Black patients would be accepted at more advanced stages with slimmer hopes of recuperating or even prematurely discharged to eventually die at home. In the year of 1934-1935, Piedmont recorded 54 patient deaths, averaging around one patient death a week. Catawba was treating more than double the patients, but only reported 39 patient deaths that year.

While the Piedmont sanatorium was unable to completely escape the clutches of discrimination, it did boast a one-of-a-kind opportunity for Black women to attend the two-year Piedmont Nurse Training Program. This school began a couple years after the sanatorium opened its doors and continued for the next four decades, educating over 300 women in tuberculosis care. The students were housed at the sanatorium and treated patients daily during their time there. The school held an elaborate ceremony in the spring for the graduates with the medical director of Piedmont and representatives from the state in attendance, such as the health commissioner. Prominent African American speakers were invited to deliver the commencement addresses. Some of the texts of these speeches have been preserved and Ewing notes that societal “issues that were being discussed in African American professional groups were present in those environments while the leaders of the white establishment are there.”

A plaque hangs in the lobby of the current Piedmont Geriatric Hospital documenting the names of all of the graduating nurses, and Ewing and his students have been attempting to track down many of these women in order to document their experiences and oral histories. Some of the graduates of the Piedmont program would go on to enlist in military medical units like 2nd Lieutenant Inez E. Holmes, a member of the 1935 graduating class. A 1942 article published in the Norfolk Journal and Guide described her as a “Modern Florence Nightingale” and “the first head nurse in a surgical ward for an African American division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.”

Trying to encompass such a rich, extensive history in a marker that cannot exceed 700 characters seems like an impossible task. Yet, it is a historic site that needs to be remembered.

“I think the issues in May and June 2020 really directed a lot of white institutions to rethink their history,” said Ewing. “To think about not only how their existence and development involved systematic exclusion of African Americans but also to recognize that there were places where African Americans made their own history, and they need to be recognized also. Retelling that story and recognizing places and spaces that are important in the history of African Americans. Particularly recognizing the Piedmont nurse training program, which is distinct in the country.”

A spot has been designated by both the Department of Historic Resources and board of the Piedmont Geriatric Hospital for the historical marker on the hospital’s property. The Tuberculosis Foundation is covering the total cost of the sign, around $2,400, according to O’Dell. Once the marker has been produced, which could take up to several months, the Tuberculosis Foundation plans on holding an unveiling ceremony on the grounds.

The Piedmont Tuberculosis Sanatorium has been a part of Virginia’s untold history, despite the thousands of African American lives it saved, shaped and educated for decades.

“A marker is a more public and durable way to realize that what you are driving by at 75 mph actually matters,” said Ewing. “It has a reason for being there that you probably don’t know because it wasn’t part of your high school history.”